Introduction

A proposal, or an offer, marks the inception of a contract. According to Section 2(a) of the Indian Contract Act, an offer is defined as a proposal: “When one person signifies to another his willingness to do or abstain from doing anything, to obtain the assent of that other to such act or abstinence, he is said to propose.”

Simply put, the person proposing is called the offeror, and the person to whom the proposal is made is called the offeree. When the offeree accepts the proposal, they become the promise.

Proposal

An offer forms the foundation of any contract. It’s the offeror’s way of saying, “I’m ready to do this if you agree.” This readiness is not enough on its own; it must be communicated to the offeree. Section 3 of the Indian Contract Act details how proposals, acceptances, and revocations must be communicated. This communication can be made through words, whether written or spoken, or through conduct.

Offers can be classified into two categories:

- Express Offers: These are offers made through clear and direct, spoken or written words.

- Implied Offers: These are offers made through actions or conduct.

Case Law

Upton-on-Severn RDC vs. Powell (1942) highlights implied offers. Here, a person received services from a fire brigade, believing the service was free. Later, it was found that the service was not free, and the person was required to pay. By availing of the benefits, they had made an implied promise to pay.

Communication of Offer: For an offer to be valid, it must be communicated. This is emphasized in Lalman Shukla vs. Gauri Datt (1913), where a servant who found his employer’s missing nephew was not entitled to a reward as he was unaware of the offer when he found the boy. The offer’s communication to the offeree must be complete for it to be actionable.

General Offer

Offers need not be directed at a specific person. As noted in Anson’s legal text, “An offer need not be made to an ascertained person but no contract can arise until an ascertained person has accepted it.” This principle is evident in the case of Weeks vs. Tybald (1605), where a general offer to marry with consent did not bind the offeror until acceptance was communicated.

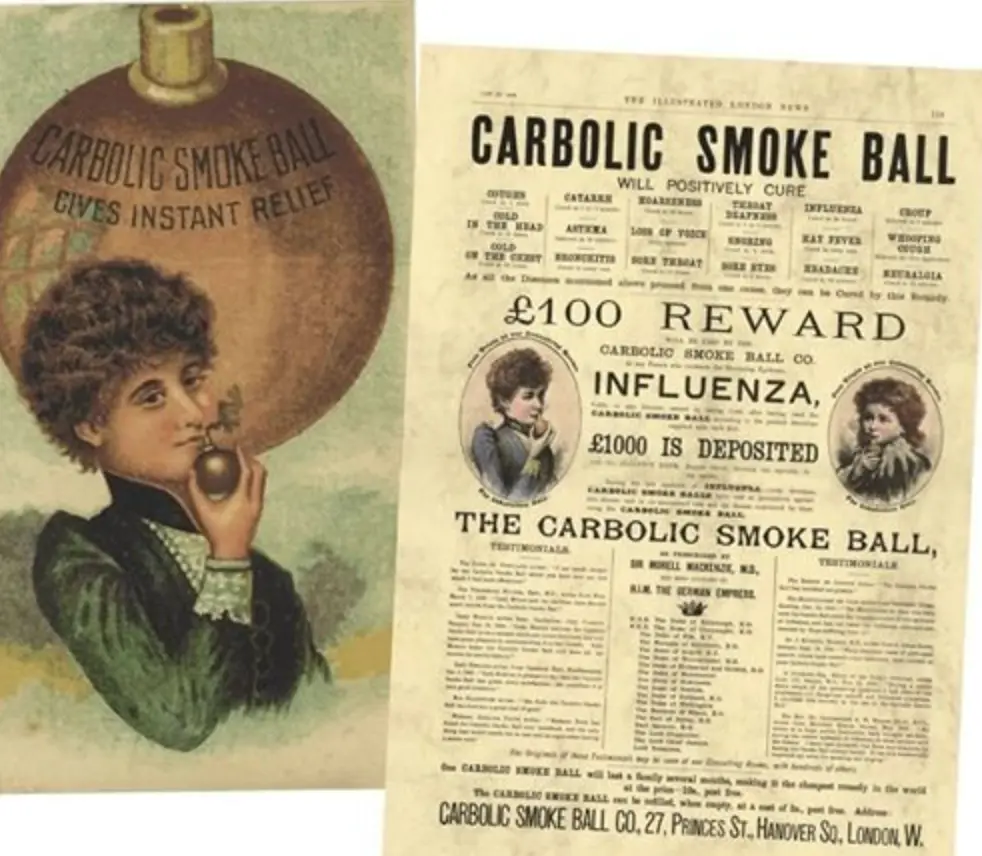

In the famous Carlill vs. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. (1893) case, the court ruled that a public advertisement promising a reward for using a product constituted a valid offer. The company’s deposit of £1000 as a sign of sincerity made the offer enforceable, highlighting that an offer can be made to the public at large and still be legally binding.

Offer vs. Invitation to Offer

Understanding the distinction between an offer and an invitation to an offer is crucial. An offer indicates a readiness to form a contract, while an invitation to offer is merely an invitation to negotiate or make an offer.

Harvey vs. Facey (1893) is a landmark case that illustrates this difference. When Harvey telegraphed Facey asking for the lowest price of a property and Facey responded with a price, it was held that Facey’s response was not an offer but an invitation to negotiate. No contract was formed as Facey had not expressed a willingness to be bound by acceptance.

A shopkeeper’s catalogue, listing prices, serves as another example. It’s an invitation to customers to make offers to buy at those prices, not a binding offer.

Conclusion

In contract law, making and communicating an offer is the critical first step toward forming a binding agreement. Whether expressed or implied, and whether communicated through words or actions, an offer must be clearly understood and accepted in order to create legal obligations. Understanding this process, as well as distinguishing between an offer and an invitation to offer, is essential for anyone navigating the complex landscape of contracts.

Also Read: Do you know the essentials of the valid contract [Click Here]

References: lawbhoomi