Introduction

The doctrine of necessity is a fascinating aspect of tort law that provides a unique defence. Let’s dive into what necessity means and how it applies in legal contexts.

What is Necessity Under the Law of Torts?

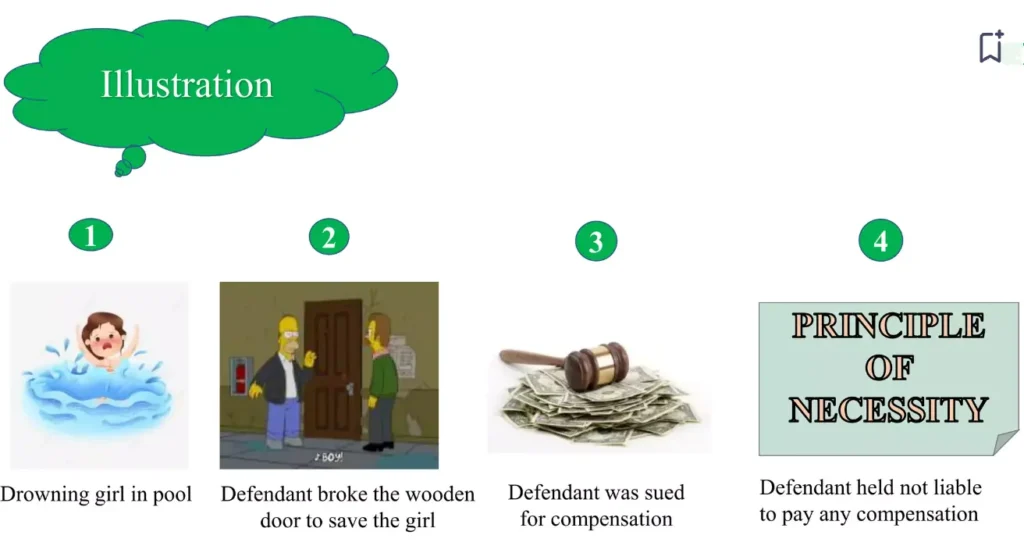

Necessity in tort law refers to a situation where a person causes harm but does so in good faith to prevent greater harm. If an act is done out of necessity, the individual responsible for the act is not held liable, provided the harm caused was not intentional. This principle distinguishes necessity from self-defence and unavoidable accidents.

Key Characteristics of Necessity

- Preventing Greater Harm: The primary goal is to prevent more significant harm. Even if the act causes damage, it is justified if it avoids a worse outcome.

- Good Faith: The act must be performed in good faith, without any intention of causing harm.

- Imminent Threat: There must be a reasonable belief that the action was necessary to prevent imminent harm.

- No Practical Alternative: There should be no practical alternative to avoid harm.

Necessity in Indian Penal Code

Section 81 of the Indian Penal Code outlines the concept of necessity: “Act likely to cause harm, but done without criminal intent, and to prevent other harm.” This means that an act done with the knowledge of potential harm is not an offence if it was done without criminal intent and to prevent other harm.

Distinguishing Necessity from Other Defenses

- Personal Defense: In personal defence, the plaintiff is directly causing injury, whereas, in the necessity, the damage is done to prevent further harm.

- Unavoidable Accident: An unavoidable accident involves damage despite all efforts to avoid it, while necessity involves intentional damage to prevent a greater threat.

Essential Elements to Prove Necessity

To successfully use necessity as a defence, the following elements must be present:

- Lesser Damage: The damage caused should be less than the harm that would have otherwise occurred.

- Reasonable Belief: The person must reasonably believe that their actions were necessary to prevent imminent harm.

- No Alternative: There should be no practical alternative available to avoid harm.

- Not Self-Caused: The person must not have caused the initial threat of harm.

Case Study: Cope vs. Sharpe

A classic example of necessity is the case of Cope vs. Sharpe. The defendant entered the plaintiff’s land to prevent a fire from spreading to adjacent property. The plaintiff sued for trespass, but the court held that the defendant’s act was justified as it was necessary to prevent imminent danger. Thus, the defendant was not liable for trespass.

Conclusion

The doctrine of necessity is a crucial defence in tort law, protecting individuals who act in good faith to prevent greater harm. Understanding this principle helps in recognizing the balance between causing minimal damage to avoid significant danger.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Doctrine of Necessity in Tort Law

1. What is the doctrine of necessity in tort law?

The doctrine of necessity lets a person avoid liability for causing harm if they act in good faith to prevent greater harm. If someone causes damage or injury while trying to prevent a more significant threat, they may not face liability, as long as they did not intentionally cause the harm and acted to avert imminent danger.

2. How does necessity differ from self-defence and unavoidable accidents?

- Self-Defence: In self-defence, the plaintiff is the direct cause of injury, whereas, in necessity, the damage is done to prevent greater harm.

- Unavoidable Accident: An unavoidable accident involves damage occurring despite all efforts to avoid it, while necessity involves intentional damage to prevent a more significant threat. The key difference is that necessity involves a deliberate action taken to prevent a worse outcome.

3. What are the essential elements required to prove necessity as a defence?

To successfully use necessity as a defence, the following elements must be present:

- Lesser Damage: The damage caused should be less than the harm that would have otherwise occurred.

- Reasonable Belief: The person must reasonably believe that their actions were necessary to prevent imminent harm.

- No Alternative: There should be no practical alternative available to avoid harm.

- Not Self-Caused: The person must not have caused the initial threat of harm.

Also Read: Inevitable Accident | Defence in Tort

Reference: toppr.com